Determining platform attempts in a Weightlifting competition

In the final days/weeks before a competition, athletes and coaches will generally discuss and make decisions about the athlete’s “competition plan”. This process can be quite simple or very elaborate depending on the importance of the competition, the level of experience of the athlete, and whether there is any need for tactics to respond to the athlete’s competitors.

At its simplest, the competition plan involves making decisions about starting weights i.e. 1st attempts on the competition platform. This is seeming simple except that it isn’t! There are different approaches that can be taken towards determining starting weights and coaches will often differ in their tactics. There are also significant differences in what athletes prefer. Some athlete prefer to trust their coaches implicitly to make decisions on their behalf on all platform attempts, while other athletes like to be involved in the decision making process. In this article, the approach taken is that the competition plan is NOT just about determining starting weights but instead a formulation of a plan for all attempts on the platform. Yes, it would true to say that some athletes do not like to contemplate these matters in advance of the competition but prefer to simply have an idea of their starting weights and then ‘go with the flow’ on the day. Arguably, this might be fine for the athlete but not for the coach. The coach needs to do some thinking about the athlete prior to the competition and develop some kind of plan. This becomes all the more important when the coach has numerous lifters to look after on the day of the event.

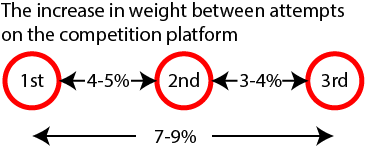

Figure 1 below and the explanation provided is one model that may assist coaches (and perhaps athletes) to formulate a competition plan. The model uses percent rather than kilos to determine the increment between platform attempts. Developing a model based on kilos would have limitations because obviously a 2Kg increase for an athlete lifting 50Kg is a great deal more significant than a 2Kg increase for an athlete lifting 200Kg. Figure 2 below provides a further illustration of this.

Assuming that the coach has a good knowledge of the athlete, an approach that can be taken is to determine starting weights via a number of steps.

The first step is to consider what might be a ‘theoretical limit” of what the athlete can achieve on the day of the competition? It is of course impossible to predict with any certainty what the athlete’s limit (maximum) will be on any day, let alone the competition day. It is a case of intelligent guess work based on key knowledge (a) what has the athlete done in training recently (b) what is their personal best on the platform (c) what is the athlete’s level of confidence in the run up to the competition (d) how does the athlete go under competition pressure i.e. psychological traits (e) what does the athlete believe they can do? (f) what is the athlete’s wellness and injury status and (g) whether the athlete is reducing in bodyweight. These are all important factors, and there are probably more. However, once a “theoretical limit” has been considered, this becomes a target to aim for on the athlete’s 3rd attempt. The pitfalls of making a judgment about the ‘theoretical limit’ are further discussed at the end of this article.

The next step is to consider the 2nd attempt. The ideal situation is that the athlete will be successful with their 2nd attempt and it will put them close but not too close to their theoretical limit on the 3rd attempt. What is too close? This is another difficult question and there are no hard and fast rules. The answer perhaps depends on a range of factors including (a) the personal traits of the athlete (b) whether there is any likelihood of tactical necessity and (c) the intuition of the coach. A 4% increase from 2nd to 3rd attempt is relatively normal. A 2% increase from 2nd to 3rd attempt would be a bit of a gamble because in effect it puts the 2nd attempt very close to the athlete’s theoretical limit. Furthermore athletes are unlikely to be happy with a 2% increase unless there is some tactical reason.

The last step involves determining the starting weight. A consideration of overarching importance is that the athlete should feel relatively at ease with their first attempt on the platform. There is never any certainty in Weightlifting but if the athlete’s level of confidence as they approach the bar is high, there is a greater likelihood of success. For this reason, it is a good strategy not to make 1st attempts too ambitious. Whereas the gap between 2nd and 3rd attempts might be 4%, it could be a reasonable strategy to increase the gap to 5% between 1st and 2nd attempts. In choosing a smaller or larger gap between all attempts, much depends on the skill and confidence of the athlete.

The above method for determining the platform attempts of an athlete depends to a large extent on making a judgment about the ‘theoretical limit’ of the athlete’s capability. As stated earlier, it is impossible to predict with any certainty what that limit might be but this does not mean that there isn’t room for the coach to make an educated guess based on available evidence. There has to be clearly identifiable reasons in the mind of the coach why the athletes ‘theoretical’ limit is greater than what they have achieved in recent training.

On the other hand, although athletes might be wildly enthusiastic about their potential in the weeks leading up to a competition, coaches must understand the reality that the opportunity to set a personal best in training is much greater than on the competition platform for the following reasons:

- The athlete can be over bodyweight in training

- The athlete can attempt a personal best in training more frequently than they can on the competition platform

- In training, the athlete can choose exactly the time interval between attempts and the exact moment of their attempt at a personal best whereas in competition they may have to wait for a long period, or be rushed if they are following themselves on the platform.

- The athlete, in their home gym, is not subjected to unusual travel as they might be when they travel to competitions.

For these reasons, coaches should be wary of estimating a ‘theoretical limit’ of performance that is greater than the athlete has achieved in recent training.