The rest interval between sets

The time interval between sets in Weightlifting training and what happens during that interval is a source of great interest to me personally and perhaps to others as well. Initially, my thoughts centred around the quest for productivity in training and the need to get as much training done in the time available. For many years I have operated on the premise that an average of 2 minutes between sets in training is optimal, and I am still of that opinion. It’s not rocket science to work out that, in any fixed period of training, an average of 2 minutes between sets accomplishes 50% more training than an average of 3 minutes.

However, in more recent years, my thoughts about the time interval between sets have expanded beyond the mere need for productivity. What has also become an interest to me is the mental process of the athlete in that time period. Furthermore, through observation and study, I have begun to formulate ideas about environmental factors that beneficially or detrimentally affect that mental process as the athlete prepares for their next effort.

It is probable that we have all experienced or witnessed the situation where an athlete in training, having completed the previous set with comparative ease, fails unexpectedly with the next set. This might happen even if there is no increase in the weight on the bar. The situation is similar in the competition environment. An athlete might succeed well with their first attempt, and be momentarily confident of the next lift, and then to seemingly suffer a loss of confidence as the wait prolongs.

While it seems clear that the time duration of the rest interval is a major factor that impacts on the performance of the Weightlifter, an explanation is needed why this is so. Furthermore, it is important to consider whether factors other than the passage of time are at work.

This article proposes that:

-

the underlying cause of performance reduction due to the passage of time is the weakening of the neural imprint or memory of the previous performance

-

during the rest period, a range of environment factors may disrupt or degrade the neural imprint of the previous performance.

- the possible environmental disruptors include sights and sounds in the gym, conversations with other athletes, the mobile phone, and interestingly the intervention of the coach.

At the heart of this proposal is the concept of a neural imprint or memory of the previous performance. Such a memory arises as a result of the activation of neurons in the brain which send electrical impulses to muscles and then receive feedback on the quality of movement achieved. Thus, for a short while after performance, there is significant neural activity within the brain. For the Weightlifter, this neural activity is a strong ‘remembrance’ of how the lift felt and, for a time, the athlete will be confident that they can repeat the performance if required. This cycle of activation and feedback is depicted in Figure 1 below.

The feedback emanates from special sensory organs located within muscle tissue, connective tissue (tendons), and joints. This feedback provides information to the brain that movement is occurring and as a result we don’t need to observe our own movement, we can simply feel it. The sensory information enables us to accurately determine the configuration of our own body at any one moment in time, and thus we can learn to achieve movement patterns with a high degree of consistency, that is we become skilled.

So, for a period immediately following performance, the brain is alive with feedback from the body. The important questions are (a) how long does that neural activity remain sufficiently strong to benefit the next performance, and (b) is it possible that environmental factors can interfere and degrade that neural activity so as to harm the next performance?

In sport, highly skilled performers are often said to operate on a sub-conscious level at least in the way movement is controlled. A high ranking tennis player does not have to think about how to swing the racket or move their feet but simply to determine where they want the ball to go. Similarly, the highly skilled soccer player does not think about the physical movement of the body required to trap or pass the ball, or make a shot a goal. Their consciousness will be centred on reading the game and deciding where to move next on the pitch. However, if a skilled performer does revert to conscious control of movement during a match invariably things go wrong, errors occur. This phenomenon is referred to as ‘choking’ or ‘constrained action’. It’s as if the performer’s own thoughts actually interfere with their performance.

For the Weightlifter, the waiting or rest period between one performance and the next poses problems. Ideally, during the rest interval, the neural activation/feedback loop is quietly and subconsciously doing its thing, that is retaining an imprint or remembrance of the previous effort. But what happens if the wait period is too long? Does the neural imprint degrade with time, and if so, how does the Weightlifter attempt to compensate?

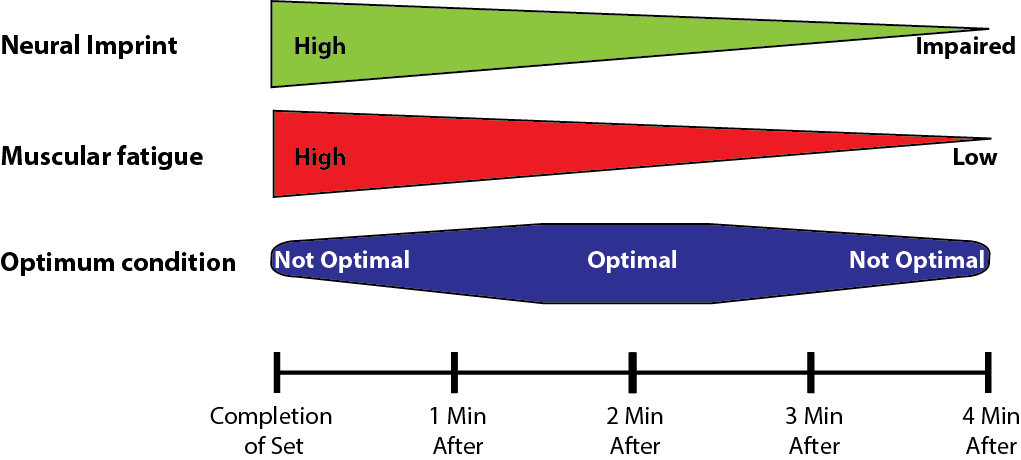

Figure 2 below hypothesises that for the Weightlifter there is an optimal wait period between performances, and it is dependant on a complex interplay between recovery of the musculature from the exertion of the performance, and the neural imprint which degrades with time (and other factors – see below).

Within the first minute after the previous performance, the neural imprint will be strong and there will be a high state of neural readiness. But also within the first minute of the wait period, the athlete will also be in a state of fatigue as energy systems replenish the energy used in the performance. Therefore the optimal time between high intensity performances is between 1½ and 2½ minutes, as depicted by Figure 2 above. But as the wait time approaches 4 minutes, although the athlete is well rested their neural readiness is beginning to fade with possibly detrimental impact on performance. For this reason, Weightlifters often have difficulty with a long wait between platform attempts.

So what does the Weightlifter do when the wait is long? It is probable that the longer the wait period, the more the Weightlifter will attempt to compensate with cognitive effort to keep the memory alive. This in term leads to the locus of control moving from the subconscious to the conscious, and an increased likelihood of a constrained action as described above.

So far, however, the discussion has mostly centred on the duration of the wait period between sets in training, or platform attempts. But what if during this wait period, the coach interacts with the athlete, for example the coach endeavours to impart technique instruction to the athlete prior to lifts of high intensity? The risk is that such technique instruction by the coach will cause the athlete to revert to conscious control of movement and interfere with the neural imprint of the previous lift causing a degradation of performance.

This does not mean that there is no place for technique instruction by coaches! But what the coach does need to think about is:

-

the timing of technique instruction/feedback (when should technique instruction be given to best advantage the athlete)

- the paramount importance of the athlete’s own sensory feedback in the development of skill and the lesser role played by verbal instructions of the coach

In addition to coach-athlete interaction, there are other possible disruptors of the neural imprint (or remembrance) of the previous performance. These disruptors include sights and sound in the gym, watching other athletes lift, conversations, the use of mobile phones, and watching video recordings of your own performance? Figure 3 below proposes that these disruptors have a cumulative effect. The more time goes by between sets, or platform lifts, the greater the potential for environmental factors to interfere with the neural imprint.

Having attempted to explain the problem of interference with the neural imprint as a result of the passage of time, or coaching interventions, or environmental factors, it is necessary to offer some guidelines to mitigate the problem? Researchers – please feel free to test!

Guidelines

Coaches should:

-

Appreciate that athletes develop skill as a result of practise, and many thousands of iterations of the neural activation/sensory feedback cycle. Therefore athletes should be encouraged to understand the importance of sensory feedback in the skill learning process and the desirability of high productivity in training to maximise sensory feedback (i.e. SHUT UP AND LIFT!)

-

Keep the athlete busy. The busier they are, the less the neural imprint after each performance will be degraded as a result of the passage of time or suffer interference as a result of their own thoughts or disruptors in the training/competition environment

- In competitions, when athletes have long waits between attempts, they should return to the warm-up room and carry out further warm-up attempts to keep alive the neural imprint of performance

-

Be careful to ensure that technical instruction given to the athlete does not slow up, delay or reduce the amount of training performed by the athlete.

- If needed, provide extensive verbal instructions about technique at the beginning of the exercise and/or when weights are very light. Avoid providing extensive technical instruction when the athlete is approaching high intensity sets so as to minimise interference with the athlete’s natural ability to learn from their own neural feedback.

- Utilise only one short/simple coaching cue prior to high intensity lifts and only if the athlete is very familiar with that cue

- Take care not to overuse coaching cues and risk the athlete reverting to conscious control of movement. If this happens failure may eventuate as a result of constrained action.

- Try to prevent the athlete overthinking, self-evaluating, asking questions, or losing focus. Such activities will increase conscious control and interfere with the neural imprint.

- Assure athletes who constantly self-evaluate their performance to be 95% error, that in fact their performance is indeed 95% correct. If an athlete associates each neural imprint with failure, they are bound not to succeed,

- Insist that athletes do not dwell on technical errors but accept that errors are a normal consequence of learning.

These days, I find myself providing less extensive technical verbal instruction but more positive reinforcement of behaviour that I feel leads to success. I provide positive reinforcement if athletes:

-

Maintain focus between sets by avoiding activities that disrupt or degrade the neural imprint created after each set

- Keep time intervals between sets with metronomic precision

- Appear to be implementing technical instruction provided by the coach, even if the result is a lift failure

- Do not engage in self-deprecation if a failure occurs

- Exert a high degree of effort on each set